#9: Final Report

We met the night before, more to dispel the nerves of being strangers than to organize a plan. I felt curiosity and welcome from the other members of our group.

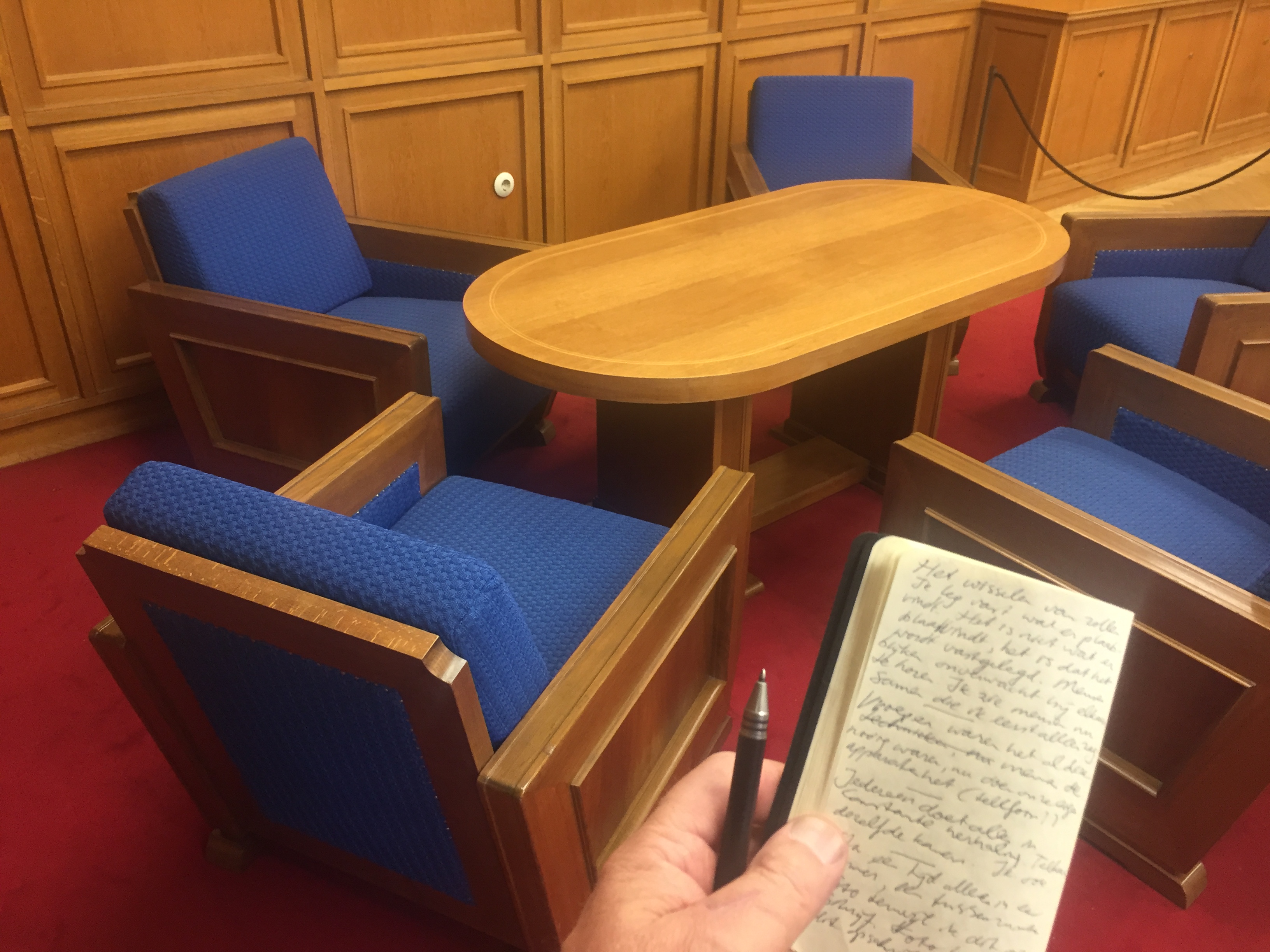

The next day we arrived at the museum and went inside to look at the exhibit. We split up almost immediately, going to different rooms and spending different amounts of time with the displays. I noticed so many levels of resonance between the architecture of the surveillance regime and the architecture and furniture of the building. I walked through the rooms of original objects, photos, and histories, entranced. I loved the details: the listening devices revealed behind doors, the stories of manipulation and betrayal. It was thrilling, unsavoury, and felt totally unrelated to our current political condition, which, given the circumstances, was a glorious relief.

The museum took care to demonstrate how thoroughly they had studied the DDR spy organization’s cadaver, everything displayed in such a way as to promise that we had conquered this regime. Drawers opened, compartments laid bare for the spectator’s gaze. This museum offered a careful simulacra of the DDR surveillance fantasy and fetish. It was like a haunted house: all the elements were designed to provoke a memory that visitors had only experienced by way of cinema: a sense of voyeuristic horror, authenticity without the risk of danger.

As we took lunch we discussed these properties of looking and the deliberate openness with which the museum conducted its affairs. One of us recounted that she had accidentally even entered the admission-ticket kiosk and stood behind the man taking money. We discussed some courses of potential actions to go forth.

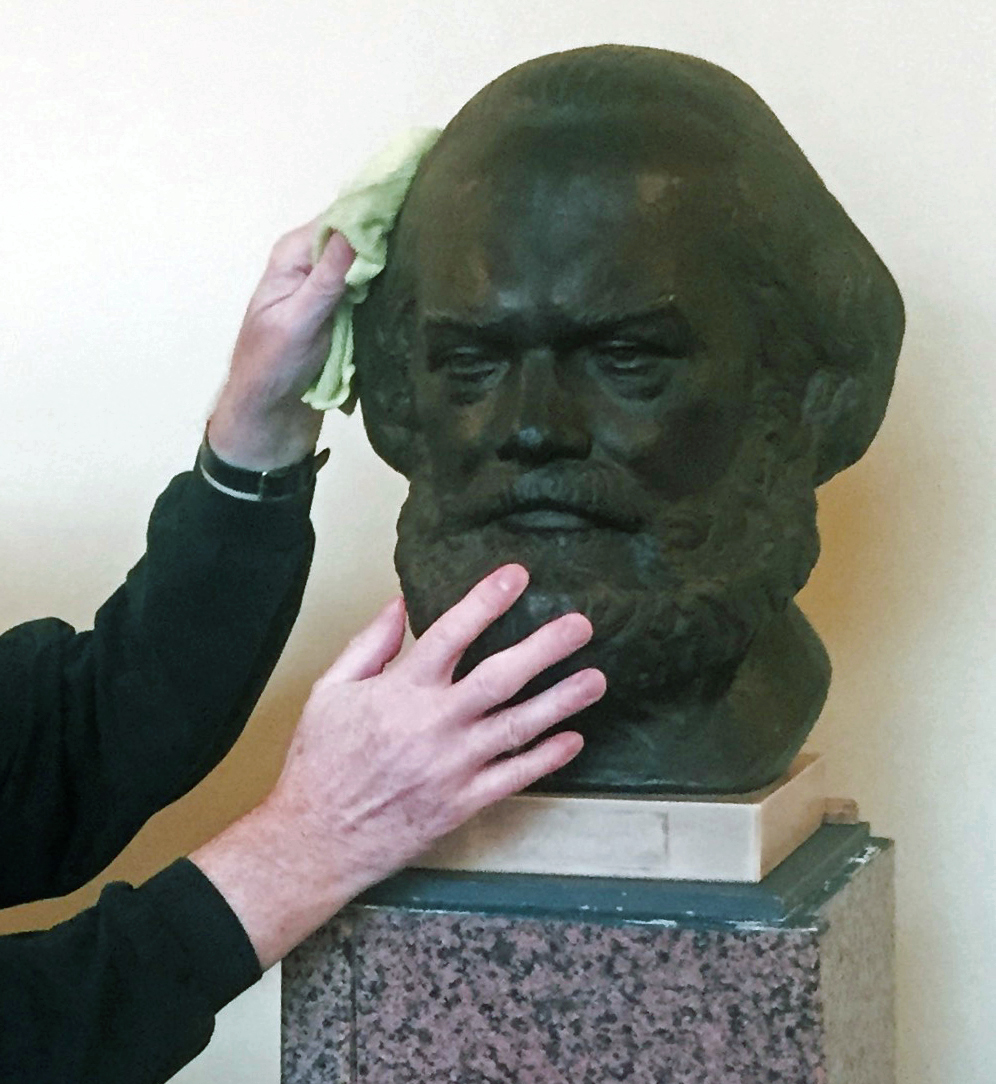

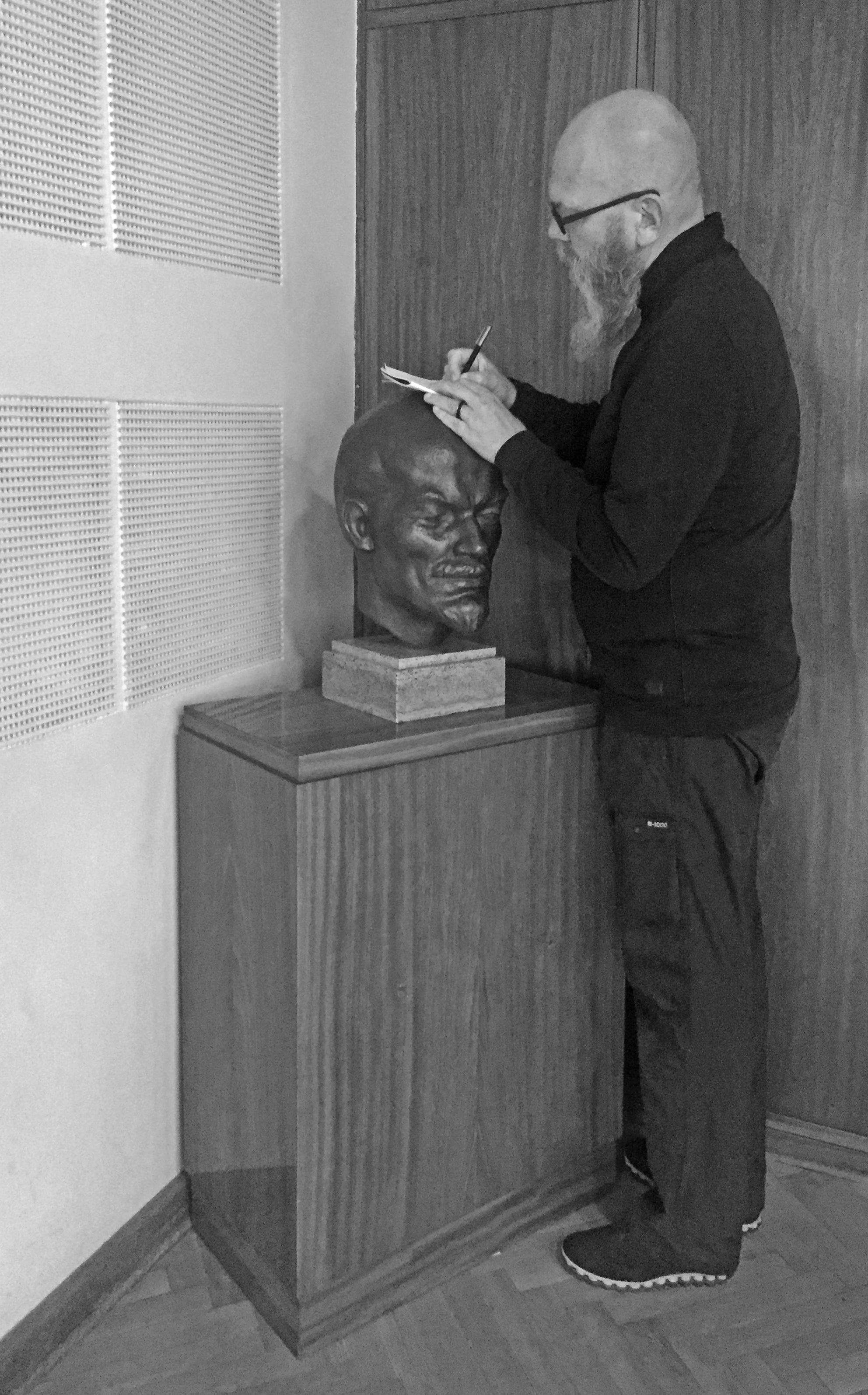

On my return I began copying excerpts from the didactic texts, both in English and German, which described particular instances of penetration, border crossing, intrusiveness, or invasion. I copied these texts onto tiny index cards. Beginning with the cloak room, where people were invited to leave their coats and bags unattended, I slipped these cards into coat-pockets, backpacks, and suitcases. It was terrifying. I then hovered around the outskirts of a tour group as the guide spoke about the complete control exercised by the regime. I approached people whose coats were trailing in their arms or those who didn’t have anyone standing behind them. I began slipping cards into pockets as people walked by, hunting unsuspecting visitors. My disguise as a visitor frayed and slipped. I began only looking for vulnerable points of access – easy pockets, open bags. Some people felt me approach and pulled away as I encroached on their personal space. It was difficult to appear to be looking at the display while my arms were pursuing another task and my whole body was racing with adrenaline. At a certain point I became completely exhausted. I joined others on the top level sitting in the largest room as they wrote. Things naturally wound down, and we ran out of energy. As we left I took a photograph of the Lenin statue holding ground in the front foyer, his hand majestically slipped inside his coat pocket.

Photos: JS