TheParallelShow TheBook

Available at JapSamBooks.nl and at your local bookstore!

#10: Sunday morning

Sunday morning. The day before, a snow storm. Now clear skies. And very cold.

We meet up at The Cloisters.

Some of us knew each other, some meet for the first time.

Steef knows Ieke, me, Frans.

Frans knows Steef, Irina, Ieke.

Ieke knows Frans, Steef, Irina.

Irina knows Ieke, Frans, me.

I know Steef, Irina, Rafael.

Rafael knows me, Ventiko.

Ventiko knows Rafael.

After a short meeting about the day we go our own ways, exploring the museum.

We meet for lunch. The Café in the Museum is closed in winter. We have to go out.

Down the steep hill. Children on sleds.

And after

back up the hill

a bit like Switzerland

not like the Netherlands.

Before we part Irina asks as us to count the steps from outside the museum up to the main floor.

Ieke gives everybody a line or two to recite as we wish.

Ventiko asks us to sometimes copy one of the others.

Frans asks for everybody to be in close proximity of each other for the first 15 min.

All still

connecting with each other.

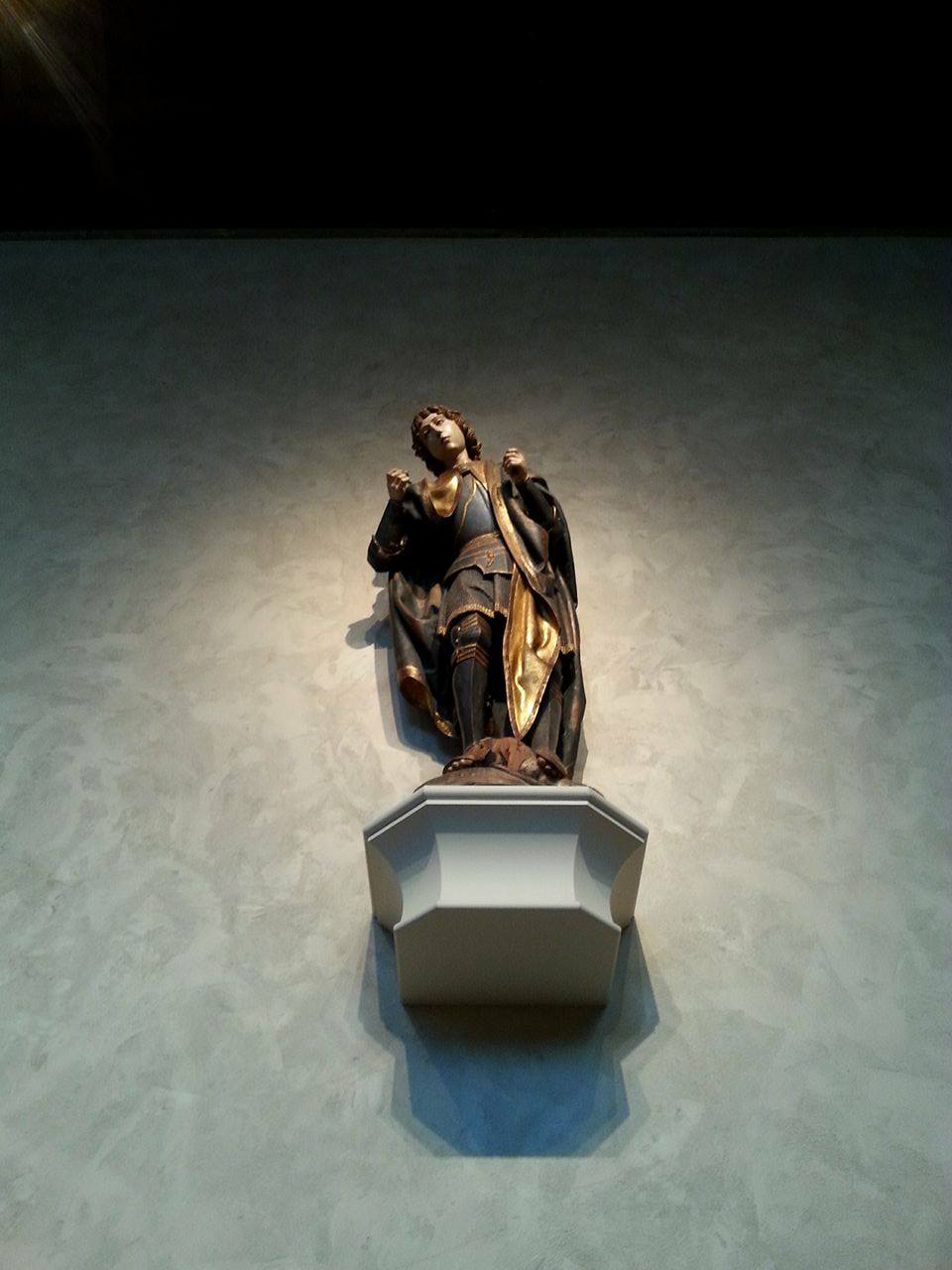

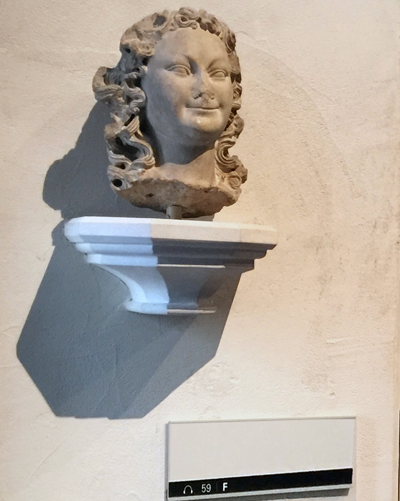

Irina asks us to smile at the figure #59.

I ask the others to join me to build a circle with the chairs in the chapel

in case they are back in lines in the afternoon.

And put them back into rows by the end of the day.

Some of us end the day with Spaghetti in my little apartment in the Lower East Side.

Photos: FvL

#10: Reimagined Reflection

To take part in the parallel show means that by default you are looking differently at the museum you visit. You have to re-establish the perimeters of your role as a visitor, because you are a performer at the same time. The museum gets a second function and with that, a different atmosphere. The space itself gains a familiarity because it is used in a different way. There is a closer involvement, an intimacy that goes further than what normal museum etiquette prescribes.

Taking parts of monasteries from various countries and several time periods the cloisters have been constructed to give the visitor the sensation of being in an old European monastery. Much like in a zoo, they have reassembled these old European fragments in a setting vaguely reminiscent of their origins. But if that ever works it certainly does not here. Most of it feels unnatural and out of place. The pieces have lost their heritage in this new reimagined state, and between all the modern additions and amenities real or fake doesn’t seem to matter all that much.

I found a small chapel room where there was a small altar with a few rows of chairs set up before it. It looked like it was meant for people to sit and pray, which to me seemed very strange. Do people pray in a museum? I found it really difficult to understand the intentions of the cloisters and in extension my place in it. So I decided to use this ambiguity I felt by approaching from different perspectives.

First I tried to see it as functional. I went to the chapel again, sat down and went through the motions of praying. Just as a structure, as a model for church behaviour. Something replicated, just as the Cloisters is. I counted down from 60 to 0, then stood up and walked out again. I went through all the rooms and tried to find their function. I warmed my hands by the fireplace, washed them in a basin and sat on benches for quiet reflection.

After this I decided to try the tourist perspective. It was my first time in the US, so maybe the American parts of this building should be my focus instead. Separately these parts are very interesting, because they are styled from a functional perspective and are subject to the collection. As a framework these parts are not designed to impress, but to facilitate.

I started by drawing a few of these places in my notebook, but then realised a tourist should really take pictures. So I then went up to other tourists and asked them to take my picture, positioning myself in such a way that only the American parts of the building would be visible.

At this point I changed course because I became increasingly interested in the clear distinction between the movements of our group and the movements of the other tourists.

Our group was quiet and focused, moving through structured tasks and repetitive motions. There was subtle interaction going on. Ieke’s lines where being exchanged, and movements where being copied by other performers. With our performances we had all somehow adhered to the nature of these spaces, moving past the fact that it was a museum. Modernising this space by our repurposing it as a place for performance seemed to fit, so I focussed on this collective movement.

Before we started I had also gotten a line from Ieke, written on a small piece of paper. I wanted to incorporate this in my movements and so I repeated this sentence in my head whilst rolling the piece of paper between my fingers. As the paper disintegrated, this sentence became fixed in my mind until finally I stopped when the paper was gone and the sentence internalised.

#10: Circulation of lines

I didn’t know much about Met Cloister, nor did I know what exhibit to expect to find there. One good thing about TPS is that it allows for an unprepared and uninformed participant. One can be ignorant at first and then find things out while visiting the place. In the first hours, while walking around, I learn that we are surrounded by medieval art works that were purchased and shipped from Europe to New York City. The pieces were placed in a building that is itself partly built out of separate ornamental pieces originating from different historical buildings of medieval Europe.

As a TPS participant my behaviour in museums differs from my regular visits to art museums. Participation makes me patient and more tolerant towards art outside the area of my interests. My focus was soon on the museum’s wall texts. Besides the facts about a work such as the techniques used, its material, country of origin, and period of creation, some texts also contain a short narration about a historical figure that the artwork represents. But what struck me in particular were the descriptions of works that mention missing parts, such as hands, arms, wings, or a baby Jesus.

In the short paragraphs of wall texts, material facts about production are combined with historic and mythological narratives, and then joined to the artwork’s current physical condition. In these texts several types of persons are also present. The first consists of the living historical figures, whether they are fictionally constructed or actually existed. Such figures include the Virgin Mary, a Bishop, a Saint, the Child Jesus, or a King. The second consists of the countless visual representations, and varied depictions that the physical artwork realizes. The third type are the makers of these visual and physical representations, some of whom have a name and others of whom remain unknown. A fourth type is the art historian, someone who oversees the writing, and a fifth the reader of a wall text.

I gave lines from wall texts to other participants. As I encountered the work, I wanted to add a sixth type of person to my list: persons who are present in the museum and embody parts of what a wall text says that are hard for me to relate to. From the wall texts that accompany the wooden carved artworks, I wrote down several short lines. I edited them by changing verbs from third person to first. To different participants I handed a different line of the result. It’s up to them whether they want to speak it out or just keep it in mind. I think of the theatrical element that this proposal entails, as it might bring us into an awkward form of role-playing. A few of the edited lines that circulated the museum were: 1)“My celebrity derives from my reputation for curing victims of plague, having myself been miraculously cured of the disease.” 2) “My hands, which would have held the infant Jesus, are carved separately and have been lost.” 3) “In my right hand I once held a lance, and my wings are lost.” 4) “The lack of attributes makes the identification of myself uncertain.” 5) “My left eye is slightly higher than my right eye, so that seen from below, both eyes remain visible and appear focused on the Child.” 6) “Whatever I once held in my hands may have been a clue to my identity.”

My line in this performance was number 2) above: “My hands, which would have held the infant Jesus, are carved separately and have been lost.” I walk in a building of architectural fragments used to construct a cloister. There are artworks here that are also incomplete and together form an exhibition of medieval art with religious themes. The wall texts are created out of multiple voices. I rehearse my line aloud in the museum’s rest room. I say my line to the other participants of this performance, when I meet them separately. In some cases an exchange of words occurs, at other times we are in an awkward situation, not knowing what to do, and we silently separate, moving on.

Ventiko’s line was number 6): “Whatever I once held in my hands may have been a clue to my identity.” She manages to point out, using her line, that food is stuck between my upper right teeth. I sit down on a bench next to a visitor and remain silent until I speak my line without looking at the person. It’s as if I’m passing on a secret code. I walk randomly up to other visitors and begin, “My hands . . .” and I show my hands. I repeat the beginning of line, “My hands . . .” Someone asks: “What about your hands?” and looks confused. I then finish the line. I try speaking it with my hands in my pockets. People are puzzled and others are curious. Someone wants to see the infant Jesus and asks me where it is.

Photos: I.T.

#10: Its Authentic Quality

The Cloisters are constructed to look like an original mediaeval clerical building. The configuration of architectural elements suggests a unity, a historic coherence, but these elements originate from very different locations and from very different historic settings. For the construction of the Cloisters, parts of at least four different buildings in France and Spain were combined. The historic accuracy seems to be less important than the historic ‘atmosphere’ it evokes.

Do the curators and visitors recognise this museum as a part of their own past, or does it merely present the existence of the other, a more anthropologist point of view? Two days earlier I visited the American Museum of Natural History and I was fascinated by the presentation of natural scenes in the beautiful dioramas. Does art and architecture in the Cloisters play the same role as nature does in these dioramas, something you are intrigued by, but you will never experience to be actually part of? In its cold and sober qualities, the original Cistercian monasteries in France evoke an experience of modesty and spirituality. The Cloisters try hard to do the same but remain a spectacle.

I prefer to look at the museum not so much to study the Middle Ages, but to understand the position of the initiators and to perceive the museum primarily as a creation of American history of the nineteen twenties and -thirties.

I consider myself a descendant of the European culture, a historic relic maybe, as much alienated from this geographic location as the artefacts in the collection.

-Sitting on a bench in the Chapter house I looked up the Rules of Saint Benedictine, the official code of monastic behaviour, and read silently.

-As I walked through the corridors and rooms I hummed the Credo In Unum Deum as I remembered it from my childhood. Some passers-by will, even unconsciously, have recognised the Gregorian melody and will in their considerations temporarily be tilted to a more spiritual level.

The Chapter House had been part of the abbey of Ponteau, a Benedictine monastery, and the last centuries been functioning as a farmers stable till it was sold and transported to New York in 1932.

-I measured the space by means of steps. I imagined I own the space and I made notes of several possible ways to furnish it as a studio: were to put my desk, my chairs and my video-screen. I checked the possibilities in relation to the available (camouflaged) outlets.

-The arches around the Cuxa cloister have glass windows. The contrast in temperature and moisture between in- and outside covers the glass with condensation. Walking around the Cuxa cloister I made small drawings with my fingers on the surface, I followed the lines and arches I could distinguish looking through. After every drawing I waited and watched some seconds for the water to drip down. Again and again I walked round the cloister to make new drawings and found that other people were copying mine. More drawings appeared and disappeared again under new layers of condensation. Inhaling and exhaling.

-At the end of the morning, all of us were silently waiting for our lunch appointment. We were sitting on benches in the corridors and in the chapter house. Nobody said a word, everyone lost in his own thoughts. There was an atmosphere of collective concentration, a reality this building was trying so hard to rediscover.

After lunch we tried to evoke this special moment again, sitting on the benches for another fifteen minutes.

It did not work at all, it had lost its authentic quality.

Photos: SvL, FvL

#10: What is parallel?

Morning.

I wonder off.

I see a guard looking intently at a tapestry.

Three female busts watching him, him watching the visitors, the visitors watching the art.

There is a chapel. Several rows of small chairs facing the windows. One chair is standing in a diagonal.

A hint?

Lets set them into a circle. One by one. In between walking away. It feels a bit like playing Mikado. Will a guard realign them?

At the end of the morning there is a circle.

Sitting. Observing. Writing a few lines in my diary:

ParallelShow – was ist parallel?

Eine Maria. Zwei Gesichter, so nahe, wie sich zu einem Kuss hinneigend.

Das Dazwischen.

Die Geschichte von Eric.

Die Geschichte von Daniel. Die Worte von Daniel.

Die Wärme hinter mir.

Die Tropfen rinnen runter.

Die Kälte und die Wärme.

Schliessen.

Das Schliessende.

Geschlossn.

Die Bank drehen.

Ein Kreis aus Stühlen.

Und die Frage, was ist parallel?

Mich sonnen in der Kälte bei grauem Himmel.

The payphone doesn’t work.

The chairs in the chapel are aligned.

I set them in a circle

over time

does a guard notice

I had a hint

one was out of alignment

four lines on the window

parallel lines in the condensation

a hint

too

After lunch.

I count 60 steps for Irina.

For the first 15 min. I sit on the floor next to the door

cross legged

my eyes almost closed>

At one point a guard comes by telling me that I have to move

I am sitting on old stones

I move onto a bench.

I say my line out loud.

Frans breaks the stillness after 15 min.

I step next to Rafael and say my line:

‘My left eye is slightly higher then my right eye so that seen from below both eyes remain visible and appear focused on the child.’

The chapel.

The chairs are realigned in lines.

I start to build a circle with them.

I pass Irina.

I read my line to her.

The figure # 59.

I smile at it.

Ieke is there too.

We read our lines to each other.

We play with them.

Fragmented.

I ask a guard

‘what is parallel?’

‘Two lines’.

He shows me with his arms

parallel.

Another guard joins

they discuss parallel together

‘two lines that don’t meet’

I ask

‘is there parallel in here?’

A moment of silence.

‘you mean what you read in the brochure

outside

it is outside

the river, on the other side’.

‘Thank you’

I ask a guard

‘what is parallel?’

‘Two lines. Two lines that never meet.’

Showing me with his hands.

‘Is there parallel in here?’

Silence. Looking around.

‘No. No, I am sorry.’

‘What is parallel?’

‘What?’

‘Parallel.’

My accent. I try again.

‘Parallel. Parallel.’

‘No. I don’t understand. Sorry.’

Steef is sitting on a bench.

A guard is talking to him. Steef must have asked her something.

I sit on another bench just like him. Arm on leg. Chin rested on the other hand.

Focusing on the guard.

She becomes the performer.

She keeps talking and explaining, moving around in the big space, turning, making gestures, pointing to this, to that.

A performance.

For us.

Eventually –

‘What is parallel?’

I ask her.

‘Things that are similar. Also lines.’

‘Is there parallel in here?’

‘Yes. Over here.’

We go into the next room.

‘Here, this is parallel. All the same period. Here a lion. Here a dragon. Here a camel.’

I ask a guard

‘what is parallel?’

‘Two lines. Like railroad tracks. Not in an angle. Like railroad tracks.’

Helping with his arms to show me the tracks.

‘Is there parallel in here?’

Looking around.

‘Yes. Yes, there is.

In between visits in the chapel.

The chairs build a circle.

Nobody seems to mind.

I sit next to Ventiko.

Sitting like her.

One leg crossed over the other.

Looking out.

Silence. Stillness.

‘My left eye is slightly higher then my right eye so that seen from below both eyes remain visible and appear focused on the child.’

Not too loud. Audible to her.

She says her line.

We mix them together.

We take them apart.

We fragment them.

We play with them.

We converse with them.

We ponder them.

Before the museum closes

all the chairs are back aligned in lines.

Facing the light.

Photos: I.D.

#10: Project 59

59 Steps:

First discovery at Cloisters was made upon arrival on the main floor after counting 59 steps from the Postern Gate Entrance to the ticketing and exhibitions. One step was outside at the door, four sets of 7 steps led to the cloakroom and the remaining 30 steps in uneven combinations, were between the cloakroom and the main floor.

Smile Back:

Due to a lack of exact dates (artworks were dated in most cases by centuries) and many anonymous authors it was not easy to find number 59 in Cloisters. Scattered audio tour points were the only visible numbers in the exposition and 59 was found in the Early Gothic Hall under a French limestone sculpture of smiling “Head, perhaps of an Angel” (perhaps from 1259 since listed as ca.1250). I smiled back.

Becoming an Angel:

The line of clean-cut beheaded angels on the arch over the entrance to Langon Chapel triggered this ironical work about our front-page issue of adequacy. The attempt to become an angel was made at a mirror in the museum bookstore.

Photos: ID

#10: A Synopsis

Yes, I arrived on time, found the artists, and got the goals for the day. I then spent 80 minutes listening to Blues Dhikr Al-Salam (Blues Al Maqam) by Catherine Christer Hennix, imagining a performance that focuses on the magic of the space and not the people or the art in it. For most museum visits, I think about the art and the people that occupy that space. I look at ripe, red mouths agape as their eyes stare at statues of soldiers, tapestries and paintings of saturated color, and I forget about my own meaning in that space.

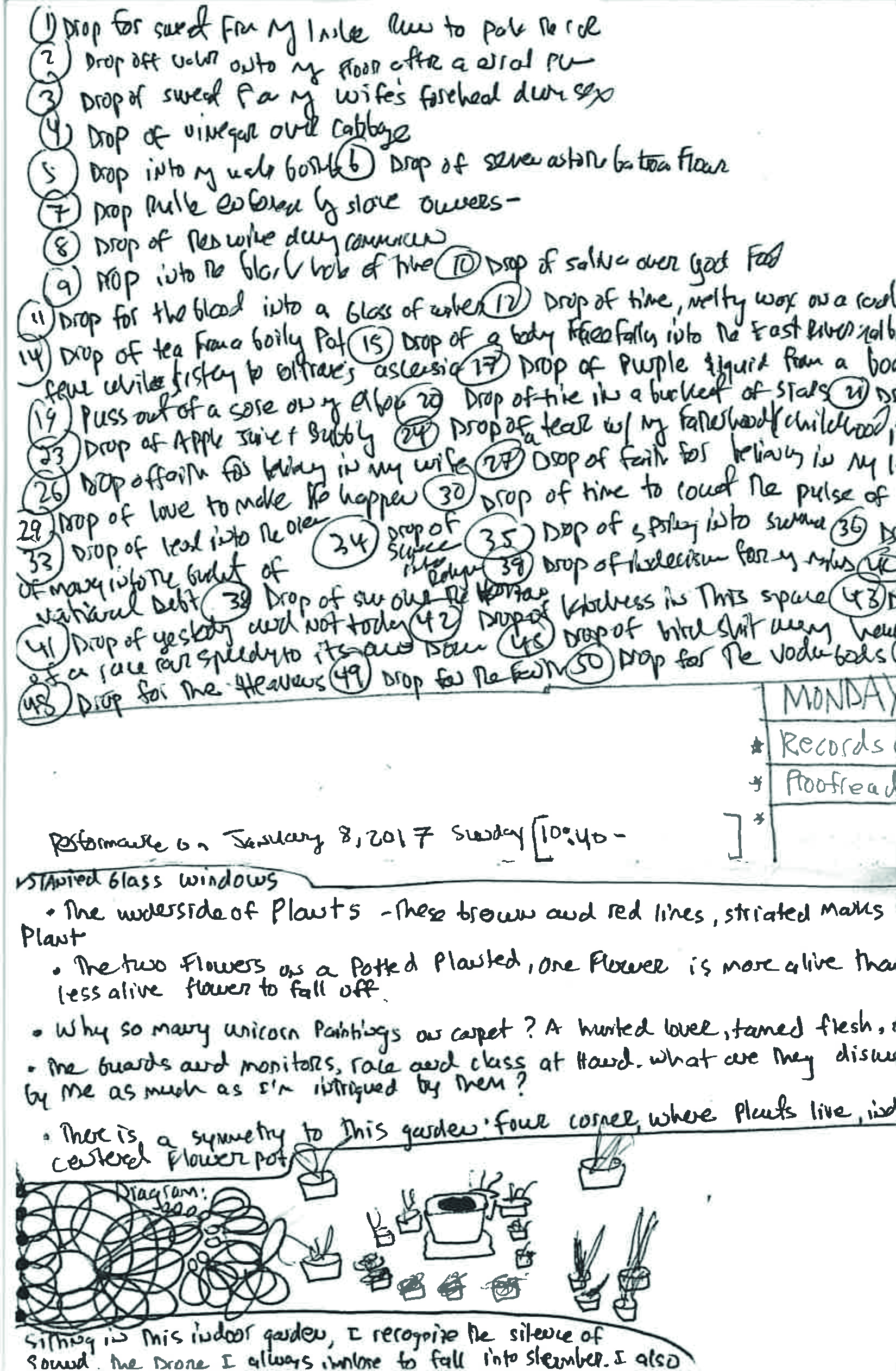

So this is what I wrote in observation of the self:

“Sitting in this indoor garden, I recognize the silence of sound, the drone I alway implore to fall into slumber. I also notice the judgement and movement. Were is the real silence coming from? If this accurate? What about real stillness with time? What is that like?… It can also be winter that generates this silence— a small space for the mind to collect the silence and sign of breath leaving the body.”

So I decided to do this performance after lunch and then make my way to resume completing chores, father obligations, and writing reports on my students.

Trace the drops of water falling down one windowpane. Imagine it is a tear, a bit of sweat, the first drops of rainfall on dry, summer pavement. List all of the imagined drops and write a narrative for at least 50 and no more than 100.

#10: Removing 7 items

I am an only child and have been entertaining myself my entire life. The trip to the Cloisters was no different.

Much of my artistic inspiration comes from historic works found in Museums. The Parallelshow brought inspiration found from the environment and those occupying it.

After the initial gathering as a group we split up for the day to perform/investigate/exist consecutively with the public without their knowledge that a performance was occurring. My first action was to take self portraits via the self timer option on my phone in the arcade while removing an object of clothing per image.

Many times before I have done similar actions and performances for my camera (and whomever may be watching) with the intention of questioning the acceptability and inclusion in an Art establishment as both a living and breathing nude female and artist making work, or if my and/or the nude female cisgender body is only acceptable if portrayed by another (often male artist) as a 2 dimensional object becoming palatable and thereby acceptable to the art goer at large.

The plan was to remove everything but the sweater and hat, which would result in a nude with an ode to my ancestry.

Until now, no one in The Parallel Show has had any knowledge of my experiment.

I was able to remove 7 items before a female security guard asked me to put on my shoes, to protect the grounds.

After watching me try and take a self portrait, she decided that I needed some directorial assistance and became part of the process. Her suggestion was to zoom in and it worked!

After we created the above shot that we both liked, I decided to move on to a new space. At this time I had noticed a creepy male guard not only observing me but circling me more than his peers.

So I headed to the bathroom:

The rest of the time before lunch was spent following other performers and watching the guests interact within the Museum.

We had a tasty lunch full of conversation and shared ideas of actions to create during the rest of the day.

I shared my enjoyment in mimicking people often without their knowledge, and unexpectedly discovered that I prefer for my intentions to remain unknown for when I encountered my fellow performers there was an expectation that the game would be played.

#9: Final Report

We met the night before, more to dispel the nerves of being strangers than to organize a plan. I felt curiosity and welcome from the other members of our group.

The next day we arrived at the museum and went inside to look at the exhibit. We split up almost immediately, going to different rooms and spending different amounts of time with the displays. I noticed so many levels of resonance between the architecture of the surveillance regime and the architecture and furniture of the building. I walked through the rooms of original objects, photos, and histories, entranced. I loved the details: the listening devices revealed behind doors, the stories of manipulation and betrayal. It was thrilling, unsavoury, and felt totally unrelated to our current political condition, which, given the circumstances, was a glorious relief.

The museum took care to demonstrate how thoroughly they had studied the DDR spy organization’s cadaver, everything displayed in such a way as to promise that we had conquered this regime. Drawers opened, compartments laid bare for the spectator’s gaze. This museum offered a careful simulacra of the DDR surveillance fantasy and fetish. It was like a haunted house: all the elements were designed to provoke a memory that visitors had only experienced by way of cinema: a sense of voyeuristic horror, authenticity without the risk of danger.

As we took lunch we discussed these properties of looking and the deliberate openness with which the museum conducted its affairs. One of us recounted that she had accidentally even entered the admission-ticket kiosk and stood behind the man taking money. We discussed some courses of potential actions to go forth.

On my return I began copying excerpts from the didactic texts, both in English and German, which described particular instances of penetration, border crossing, intrusiveness, or invasion. I copied these texts onto tiny index cards. Beginning with the cloak room, where people were invited to leave their coats and bags unattended, I slipped these cards into coat-pockets, backpacks, and suitcases. It was terrifying. I then hovered around the outskirts of a tour group as the guide spoke about the complete control exercised by the regime. I approached people whose coats were trailing in their arms or those who didn’t have anyone standing behind them. I began slipping cards into pockets as people walked by, hunting unsuspecting visitors. My disguise as a visitor frayed and slipped. I began only looking for vulnerable points of access – easy pockets, open bags. Some people felt me approach and pulled away as I encroached on their personal space. It was difficult to appear to be looking at the display while my arms were pursuing another task and my whole body was racing with adrenaline. At a certain point I became completely exhausted. I joined others on the top level sitting in the largest room as they wrote. Things naturally wound down, and we ran out of energy. As we left I took a photograph of the Lenin statue holding ground in the front foyer, his hand majestically slipped inside his coat pocket.

Photos: JS