#10: Circulation of lines

I didn’t know much about Met Cloister, nor did I know what exhibit to expect to find there. One good thing about TPS is that it allows for an unprepared and uninformed participant. One can be ignorant at first and then find things out while visiting the place. In the first hours, while walking around, I learn that we are surrounded by medieval art works that were purchased and shipped from Europe to New York City. The pieces were placed in a building that is itself partly built out of separate ornamental pieces originating from different historical buildings of medieval Europe.

As a TPS participant my behaviour in museums differs from my regular visits to art museums. Participation makes me patient and more tolerant towards art outside the area of my interests. My focus was soon on the museum’s wall texts. Besides the facts about a work such as the techniques used, its material, country of origin, and period of creation, some texts also contain a short narration about a historical figure that the artwork represents. But what struck me in particular were the descriptions of works that mention missing parts, such as hands, arms, wings, or a baby Jesus.

In the short paragraphs of wall texts, material facts about production are combined with historic and mythological narratives, and then joined to the artwork’s current physical condition. In these texts several types of persons are also present. The first consists of the living historical figures, whether they are fictionally constructed or actually existed. Such figures include the Virgin Mary, a Bishop, a Saint, the Child Jesus, or a King. The second consists of the countless visual representations, and varied depictions that the physical artwork realizes. The third type are the makers of these visual and physical representations, some of whom have a name and others of whom remain unknown. A fourth type is the art historian, someone who oversees the writing, and a fifth the reader of a wall text.

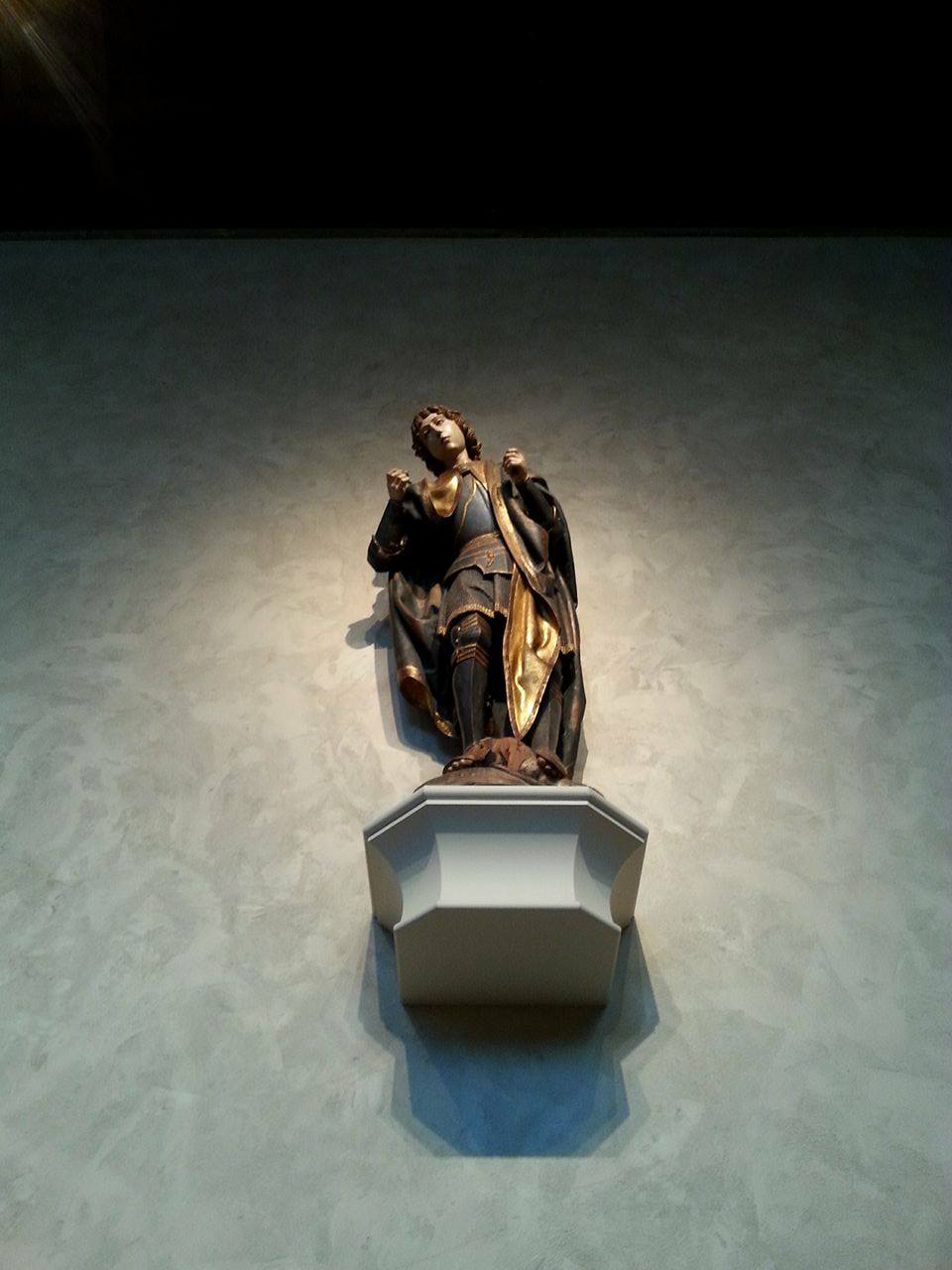

I gave lines from wall texts to other participants. As I encountered the work, I wanted to add a sixth type of person to my list: persons who are present in the museum and embody parts of what a wall text says that are hard for me to relate to. From the wall texts that accompany the wooden carved artworks, I wrote down several short lines. I edited them by changing verbs from third person to first. To different participants I handed a different line of the result. It’s up to them whether they want to speak it out or just keep it in mind. I think of the theatrical element that this proposal entails, as it might bring us into an awkward form of role-playing. A few of the edited lines that circulated the museum were: 1)“My celebrity derives from my reputation for curing victims of plague, having myself been miraculously cured of the disease.” 2) “My hands, which would have held the infant Jesus, are carved separately and have been lost.” 3) “In my right hand I once held a lance, and my wings are lost.” 4) “The lack of attributes makes the identification of myself uncertain.” 5) “My left eye is slightly higher than my right eye, so that seen from below, both eyes remain visible and appear focused on the Child.” 6) “Whatever I once held in my hands may have been a clue to my identity.”

My line in this performance was number 2) above: “My hands, which would have held the infant Jesus, are carved separately and have been lost.” I walk in a building of architectural fragments used to construct a cloister. There are artworks here that are also incomplete and together form an exhibition of medieval art with religious themes. The wall texts are created out of multiple voices. I rehearse my line aloud in the museum’s rest room. I say my line to the other participants of this performance, when I meet them separately. In some cases an exchange of words occurs, at other times we are in an awkward situation, not knowing what to do, and we silently separate, moving on.

Ventiko’s line was number 6): “Whatever I once held in my hands may have been a clue to my identity.” She manages to point out, using her line, that food is stuck between my upper right teeth. I sit down on a bench next to a visitor and remain silent until I speak my line without looking at the person. It’s as if I’m passing on a secret code. I walk randomly up to other visitors and begin, “My hands . . .” and I show my hands. I repeat the beginning of line, “My hands . . .” Someone asks: “What about your hands?” and looks confused. I then finish the line. I try speaking it with my hands in my pockets. People are puzzled and others are curious. Someone wants to see the infant Jesus and asks me where it is.

Photos: I.T.